What if We Turned the Sunset Into Paris?

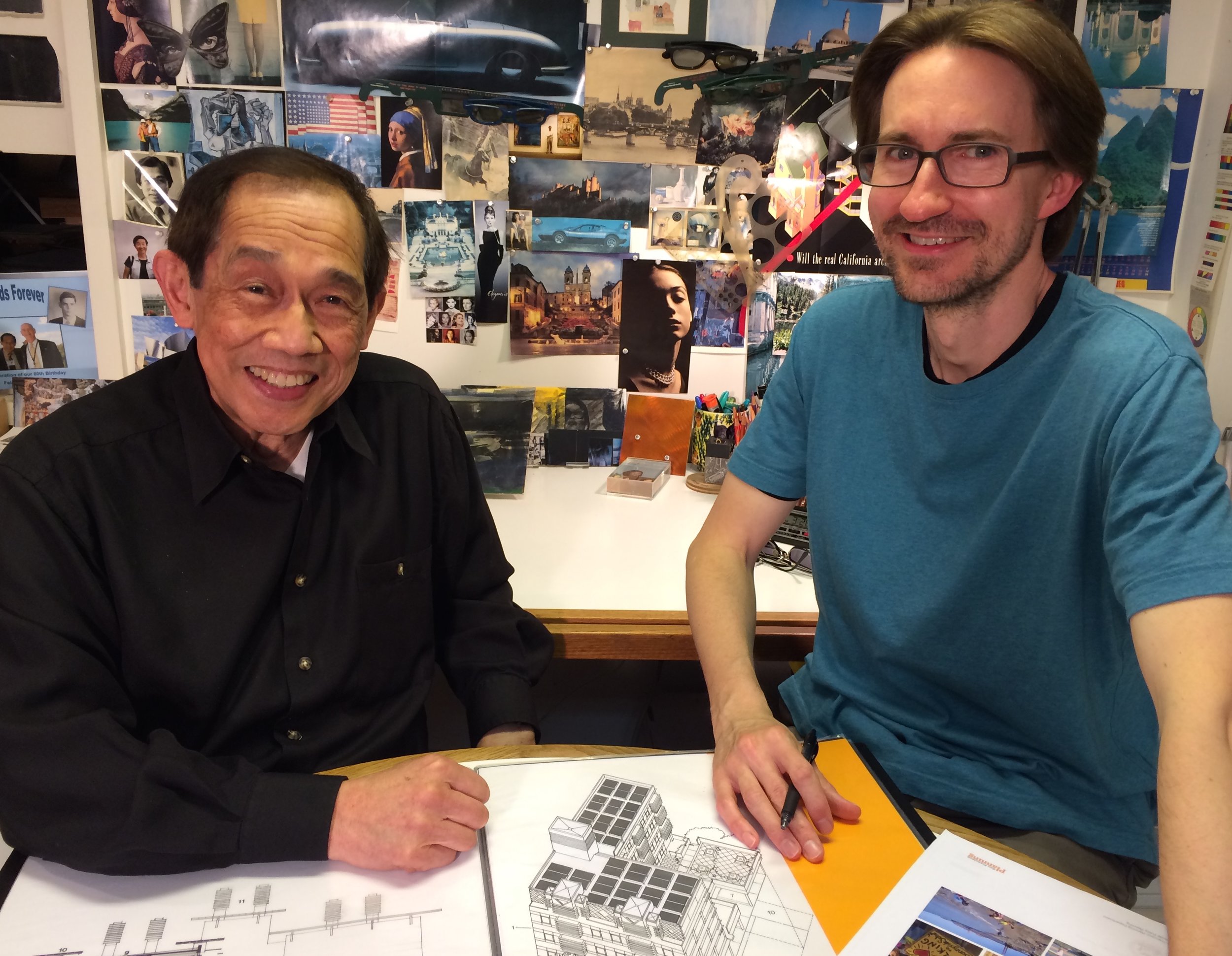

Retired architect Eugene Lew and his assistant James Pitts have designs to help middle-income families afford a home in San Francisco.

By Joel P. Engardio

On a peninsula as tiny and popular as San Francisco, it’s difficult deciding how to fit everyone who wants to live here.

Sometimes, we embrace a truly Big Idea — like when we tunneled through Twin Peaks 100 years ago to connect a barren westside with commuter trains downtown. Back then, the Sunset District was just miles of sand dunes to the ocean.

Rows of small, attached homes covered the sand by the 1940s. They would support a great middle class population for decades. But the kids and grandkids of those working families are struggling to stay in San Francisco now that a Sunset starter home costs more than $1 million.

Maybe it’s time for the next Big Idea.

Retired architect Eugene Lew wants us to reimagine the Sunset for the modern middle-income family. Look past the houses with only one bathroom and the paved over, treeless yards. Forget the moribund business districts and trains that abandon passengers to switch back where demand is higher.

Lew envisions a greener Sunset with vibrant commercial corridors and abundant train service supported by thousands of new families living in his building design. He calls it Dom-i-city for “Domiciles in a city.” Each six-story structure features a garden courtyard and enough three-bedroom/two-bath units for 15 families — all within the footprint of three standard Sunset homes.

Big ideas are supposed to be bold.

They also come with big obstacles. How do you sell six stories in a city that loves to defend its two-story neighborhoods? Who will give up their single-family home to make room for a Dom-i-city building? What can make the units affordable?

Before answering, Lew asks skeptics to describe their best city experience.

“People go to Paris and say how much they love it, but have no idea the housing was 80 feet high. They say it didn’t feel that tall,” Lew said. “Yet in San Francisco we argue about 40 and 60 feet. Housing policy shouldn’t be an arbitrary height limit. It should define how we want to live so we can build toward that ideal.”

Lew’s design focuses on creating mini-communities and making family life easier. The units are 1,200 square feet with an open kitchen, laundry, walk-in storage closet, two bathrooms and three real-sized bedrooms. An interior courtyard sits on the roof of the first floor garage, protecting residents from wind and traffic. Concrete construction provides fire safety and soundproofing. There is an elevator.

The ground floor includes parking for each unit, a small apartment for short-term rentals to help cover maintenance expenses and even a music practice room for kids with squawking instruments. There’s also a multipurpose area for child day care, a senior center or neighborhood store. Any percentage of the parking could be turned into more commercial space if the building is on a transit corridor.

As a parent, Lew knows families prefer neighborhoods to high rises. That’s why his design is the right balance between capacity and scale. “At five stories,” he said, “you can still whistle to your kid playing in the courtyard and call him for dinner.”

As a senior, Lew knows his generation will find downsizing more attractive if there’s an elevator building in the neighborhood. He is hopeful seniors will accept a free unit in exchange for their Sunset homes to make room for Dom-i-City construction.

Dom-i-city depends on voluntarily participation and the biggest hurdle will be recruiting early adopters. But Lew said he is confident many will want their own after seeing the first one.

Of course, it will be easier for Lew to start with empty land — like the 17 acres at the Balboa Reservoir. Housing is proposed for the westside site, but stakeholders have yet to agree on a final plan. Dom-i-city’s family-friendly design could give the community something to rally around, especially if it was presented as “five blocks of Paris on the old reservoir,” Lew said.

Other opportunities for Dom-i-city include teacher housing on surplus school lots and in-fill development along westside transit corridors. The Richmond District also suits Dom-i-city, with its Sunset-like street grid of attached homes. But the Sunset already has two underutilized Muni train lines — providing the transportation solution that new housing requires.

Affordability for middle and moderate-income families is central to the Dom-i-city plan, which Lew detailed in an online white paper. He wants to use private-public development and the power of shared equity. In short, buyers would pay for part of the home’s total cost and a silent long-term investor would pay the rest. They would proportionally share proceeds from a future sale.

Lew doesn’t have a financial stake in the project. He ran a successful architecture firm and enjoys a comfortable retirement. This is about giving back. Lew hopes his volunteer assistant, James Pitts, will be the first Dom-i-city resident.

Pitts and his wife are tech workers who want to start a family but can’t afford to buy a house. They represent a generation of young families leaving San Francisco and Lew wants to stop that trend by building more middle-income housing now.

“It can feel like tilting at windmills because the only way to solve our housing problem is to get people to accept a lot of change,” Lew said. “People fear change when they look at it in terms of loss. But Dom-i-city shows us what we will gain.”